Foreword

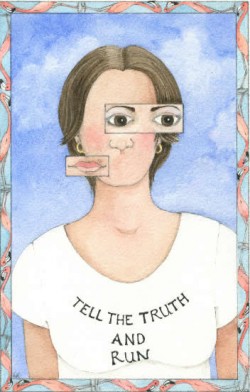

The diagnosis of mental illness is painful to hear. However, study after study brings new opinions as to its nature and source. A popular paradigm circulating among psychiatric circles suggests the condition of hearing voices is not always pathological, and many high-functioning voice hearers do not come forward, nor do they tell anyone, for fear of being discriminated against or anathematized.

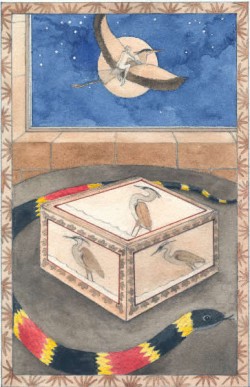

This story is about one of those people. This is not a story about paranormal powers, nor is it fantasy or magic realism. This fictional piece is taken from the real world, the scientific world, and the South Florida cultural landscape, except for my theory about the slippers who live on the neuronal roads and vast unknown spandrels of the brain. The reader does not have to believe in slippers…but I do.

Chapter 1

The Blue Goose

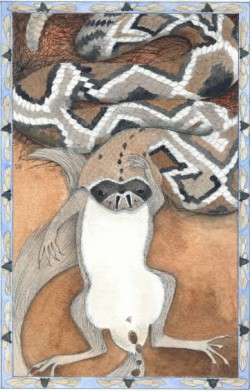

One hundred miles up the coast, another man, Aubrey Shallcross, leaned over the sink in his bathroom and pulled on something, too—a sliver of meat between his teeth. When he was young with milk teeth, he was teased at swimming lessons over the dark moles on his body, so his devout Catholic grandmother told him a grandmother story to anneal his child confidence. She said the moles were the tops of angels’ heads, guardian types, and he was especially lucky because most children have only one angel, but he had many, if you read the moles right.

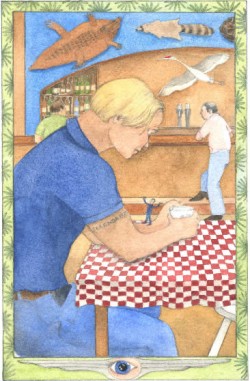

The boy, Aubrey, chose a peppercorn-looking thing in his left armpit as his first-string seraph and secret friend, then in his mind, changed the mole into a three-inch-tall man in a three-piece suit like the one his father wore to Mass. He named the little man Triple Suiter. Unrelated to this, Aubrey went on to develop what Western society calls schizophrenia.

Chapter 4

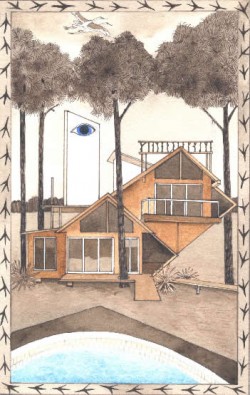

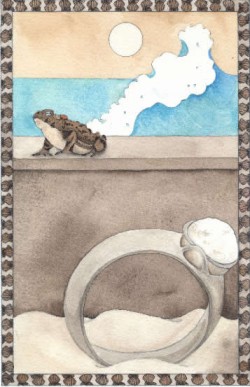

He owned a photographic and audiographic mind, one that designed words, run-on sentences, himself, tree lines, highway art, still life, and torn skin—all in a cranial ring of benign madness with his sacred sidecar and consigliere, Triple Suiter. His head was a builder, a wild whittlewright and comic bettersmith, and his two-story house, O’gram, was the wood-frame manifestation of what he really was up the stairs: an unencumbered freebaser of the calcium toadstone rock that bore down on his red-means-wrong senses every day, slimming things to take down his throat as an honest-to-God practitioner of that marvelation of sensation and derangement. He would throw the gas on anything and light it, this rainstorm inside a flipped car, this connoisseur of the psycho-generated souvenir who also had a powerful fear, because with carburetion like that, you easily could be unhorsed and chased through the doors of your own rectum when the wrong whittle monster got loose.

Chapter 9

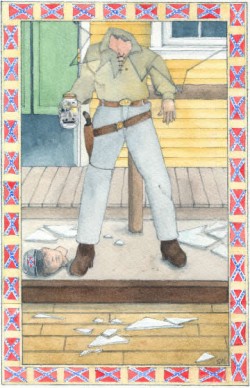

That same afternoon, The Junior leaned against the wall of his jail cell, blue and beleaguered. He tried to remember stories from the True magazines he’d read as a boy describing the ways outlaws died or committed suicide when they were surrounded or incarcerated like him.

The cowboy culture had a long, oral tradition of last stands and taking one’s life as the law closed in. The Junior knew the law wasn’t aiming guns at him; he was only in for two weeks, and that wouldn’t look good next to someone who chose self-murder because they had been sentenced to forever without parole. So he quit it—shifted into a serious drifty and watched an empty spool of bullet chambers turning on the cell wall in a narrated film piece. It told him to open the spool, insert a bullet, spin it on his thoughts, and see what happens to the trigger when the Ouija finger gets loose.

He saw Marla riding her grand prix horse high off the ground in flying changes every stride. Her hair shook in the suspended moments.

“Look at her, that beautiful woman. God a mighty, I’m murdered,” he said in the Clorox-soaked air.

He blamed the horse for taking her away, so he spun the gun chambers in the film and aimed at the horse’s head. Click! But the hammer landed on an empty chamber.

“I hate that damn horse. Why’s this roulette let it live?” He rolled the chamber again and aimed it at his own head. It occurred to him how old he was, and she was where he couldn’t surround her with his bad-boy reputation.

“Bang,” he said, and the blast blew out half his brains. “I hate it, goddamnit. I hate it.”

That night in his sleep, a woman came to him and held his head on her lap. She had held him before—in a jungle camp years ago when he was tied flat to a platform by his captors. After two days, a man walked into camp and shot those who held him captive. The man was South Vietnamese. The woman who held his head while he slept was a slipper.

The next morning, light flooded his jail cell. He walked over to the stainless-steel mirror above the sink and began to hear the fear, the Florida kid fear: cicadas—what Christaine could hear like a thousand dripping night faucets, the terrible tinnitus—that malarial sound that never leaves a child, even if they move away, yet no one notices it when they are happy and sane.

The Junior turned from the mirror and mumbled, “I was once, but I ain’t now”—the genuine redneck inverse of cogito, ergo sum.

He thought about the people he knew he killed—and must have killed—in Vietnam and felt bad.

A head song came. It was Neil Young, the bleater, singing about the old man looking at his life and needing someone to love him. The Junior knew he was the old man in that song now, not the young man singing it to the old man anymore. Worse, he was a broke old man in jail, staring into a suicide-proof mirror with a shoddy shine job that dragged out his features—put there by the state of Florida and the lowest bidder so he couldn’t cut his tax-paying wrists.

He studied his face more and got ahold of what he really looked like on the slow downside slide of forever young.